Today's resource-conscious consumer is always eager to find new & improved ways to save the environment while saving a buck. As it turns out, using drip irrigation can be one of the main at-home or do it yourself steps which simultaneously addresses the broader issues surrounding water management and water conservation. Used in conjunction with adequate mulch and a properly functioning system, drip irrigation becomes the circulatory system in the garden, the veins of the organism of your garden. In this short article we will be discussing some of the common techniques we use to minimize costs and maximize results using soft-line, drip irrigation to provide water delivery to low water plants in the San Jose, San Fransisco Bay area climate.

Many of our customers are in the process of revitalizing some aspect of their landscape, weather it be a small bed, the front garden or the entire landscape, one thing is certain; the need for correct installation and adjustment of drip irrigation can make the difference between a successful garden and the potential alternative. Thankfully, many of the low water and California Native Plant selections are famously tough, so even when running dry or suffering from other adverse conditions, the plants tend to hold up rather well.

Waste Not, Want Not: Dollar By Dollar, Drop By Drop

Drip irrigation also has the advantage of being low pressure, meaning that in ideal conditions one can get away with watering quite a few plants with only one valve. Also, being that most drip heads are flow adjustable, meaning they can be fully adjusted or closed completely with no need to change anything at the valve. In conventional landscaping (you'll note the use of "conventional" in association with turf-lawn) one would need a separate valve for every area. With drip, this becomes a non-issue as water can be adjusted for each and every plant or closed completely.

In terms of water application the difference between conventional turf-lawn spray and drip irrigation is notable: Spray is measured in gallons per minute, whereas drip is measured in gallons per hour. That means that conventional pop-up or radial spray heads can use up to five times more water over the same time period; notable indeed. Add to this the fact that conventional turf-lawn not only takes more water at the root level to keep happy, but also loses more water out of its own surface area as the water heats up and vaporizes. It's not hard to see how the potential savings of using low water plants extends far past the up-front savings in water delivery.

Transpiration & Evaporation: The Real Issues

There are a few simple values common to all plants, which we need to take into account when diagnosing the water delivery needs in the landscape: Temperature, humidity, wind, soil moisture and type of plant. We call the group of these values local to your garden the "micro-climate".

According to the USGS:

"10 percent of the moisture found in the atmosphere is released by plants through transpiration."

Transpiration is the process by which moisture is carried through plants from roots to small pores on the underside of leaves, where it changes to vapor and is released to the atmosphere. Transpiration is essentially evaporation of water from plant leaves. Transpiration also includes a process called guttation, which is the loss of water in liquid form from the uninjured leaf or stem of the plant, principally through water stomata.

Evaporation is the process by which the surface of water is heated and slowly turned into vapor. Evaporation accounts for 90% of the water returning into our atmosphere mainly from the surface of the oceans, lakes and other bodies of water.

HOW TO

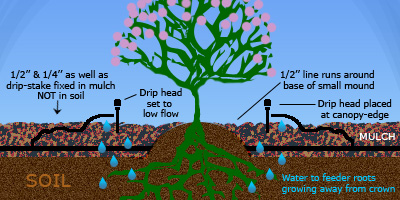

Use 1/2 inch softline, then run to each plant with 1/4-inch tubing.

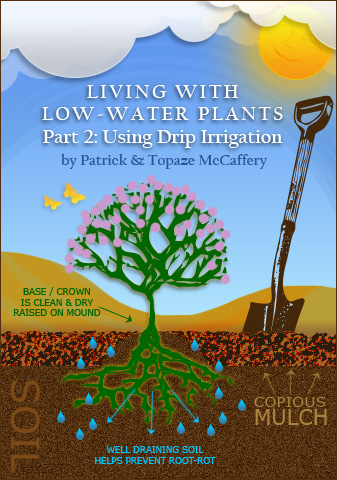

Bury softline in mulch, not in the grade. Run the 1/2'' line around small mounds.

Remember: Keep all emitters above grade. Burying emitters in soil can lead to the emitters being eventually clogged.

Ideal drip zone in between the crown & edge of canopy; feeder roots actually move away from the crown (center) of the plant, which means that water delivery should take into account not just the area within the canopy, but also slightly outside the canopy.

Drip irrigation is ideal because of adjust-ability to each plant, ease of installation and low up front costs.

Most people think drip is used primarily in vegetable garden applications, but in fact we use drip exclusively unless there is a large grass area or if there is specific need to field-broadcast water. This is a notable issue for anyone interested or concerned with water management. As we touched on in the previous installment, adding mulch periodically keeps roots covered and builds soil. It also serves to insulate the plants roots and the microorganisms which thrive in the soil.

The drip heads that we prefer to use come in two varieties, 360* spider-stream and 360* spray. Since most drip heads are adjustable in gallons-per-hour (rather than gallons per minute as with conventional pop-up spray heads for turf) we tend to use the ones with the broadest flow rage, which usually ends up being 20 gallons per hour.

The spider-stream drip we use where we want an even distribution in a small area, usually delivered to the roots of a single plant. The 360* micro-sprays are good for wider areas or larger clumps of ground cover which necessitates overhead spray.

For a more technically complete review of drip irrigation systems visit: The Urban Farmer Store

See more in our Living with Low Water Plants series:

Part 1: Plant Installation Part 2: Using Drip Irrigation

Part 5: Holistic Economics

All content (c)2010 Patrick & Topaze McCaffery

No comments:

Post a Comment